January 14th, 2021

Quick Stock Overview

Fortescue Metals Group

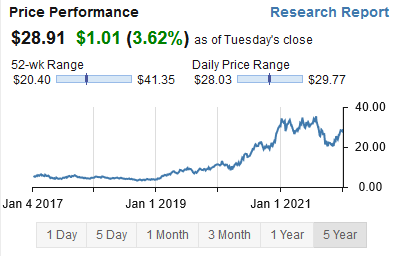

Ticker: FSUGY

Source: www.stockrover.com

Key Data

| Sector | Basic materials |

| Industry | Other industrial metals & mining |

| Market Capitalization ($M) | $44,159 |

| Price to sales | 2.0 |

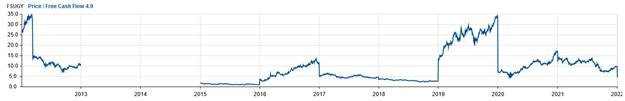

| Price to Free Cash Flow | 4.9 |

| Dividend yield | 18.2% |

| Sales ($M) | 22,231 |

| Net Cash per share | $1.72 |

| Equity per share | $11.51 |

| P/E | 4.3 |

| ROIC | 51.3% |

| Free cash flow/share | $5.96 |

Rio Tinto Group

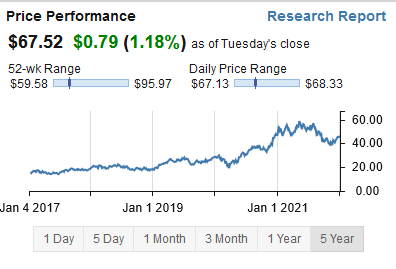

Ticker: RIO

Source: www.stockrover.com

Key Data

| Sector | Basic materials |

| Industry | Other industrial metals & mining |

| Market Capitalization ($M) | $107,842 |

| Price to sales | 1.9 |

| Price to Free Cash Flow | 6.4 |

| Dividend yield | 10.2% |

| Sales ($M) | 58,332 |

| Net Cash per share | $2.43 |

| Equity per share | $32.71 |

| P/E | 5.9 |

| ROIC | 28.9% |

| Free cash flow/share | $13.68 |

Investment Thesis

Betting on atoms

As the S&P500 and Nasdaq have regularly hit new highs, it’s become a pretty standard position for value investors to warn of a bubble. Other investors even say value investing is dead. As if stock market valuations weren’t enough, there’s Bitcoin, alt-coins, NFTs, meme stocks, real estate, and countless other signs of irrational exuberance.

The big winner of this irrational optimism has been tech stocks. From profitless startups to FAANGs behemoths, it’s been a great year for software investments. Comparatively, the “real” stuff is pretty much dismissed as being too old or boring. Blockchains, data centers, and the coming all-encompassing virtual reality are where the future is.

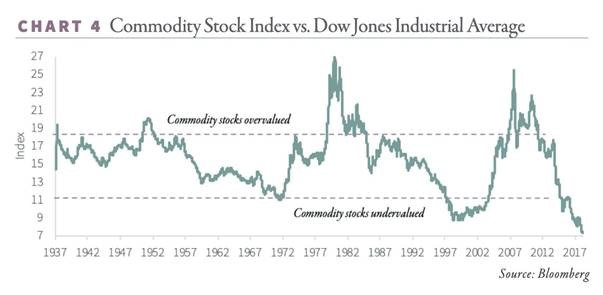

Do you want to own a company that builds the “metaverse” or do something more mundane? Investors have already declared loudly that they prefer digital at any price. Never before in history have commodities been undervalued compared to financial assets.

Source: The Felder Report

I’m skeptical, though, that we’ll be able to do away with the material world anytime soon. Virtual reality glasses, electric cars, and computers still need real materials to make them. Our Amazon deliveries travel on real roads and go over real bridges. All our data centers are powered by copper cable hanging from steel pylons.

My first stop was to look at some of the biggest mining companies that produce the metals we need. No matter whether the BBB “Build Back Better” bill passes in Washington, the developed and developing world hunger for metal isn’t going away. Despite China’s building period ending, a lot of infrastructures are still needed in South-East Asia, the Indian subcontinent, South America, and Africa.

I discovered that mining companies are very profitable, paying out double-digit dividends and selling at fire sale prices.

This report first appeared on Stock Spotlight, our investing newsletter. Subscribe now to get research, insight, and valuation of some of the most interesting and least-known companies on the market.

Subscribe today to join over 9,000 rational investors!

Chapter 1: Narrowing down

Can mining be ethical?

An obvious reason for investors’ distaste for heavy industries is their public image. Mining is usually associated with devastated landscapes, pollution, and fumes that obscure the horizon. These shareholders are ruthless capitalists who destroy the environment out of greed and ruthlessness.

Honestly, some of this image is well-deserved. Over the course of history, mining has been carried out in a careless and polluting manner. There are still many unscrupulous companies operating this way, especially in poor and/or corrupt countries.

A number of mining companies are now taking steps to clean up their act. They realized that if they were to avoid further problems down the road with activists and governments, they would have to respect local communities and the environment. Additionally, technological advances have made it possible to develop safer, cleaner practices.

Those companies are recognizing that now, if they hadn’t before. As an example, the head of Rio Tinto, one of the two companies covered in this report, was dismissed in 2020 for destroying culturally significant Aboriginal sites. As for his successor, you can bet that he will be much more careful to keep his job.

Therefore, I believe that mining investing is not automatically unethical as long as we invest in companies that are large enough to be forced into adopting better practices.

The need for more metals

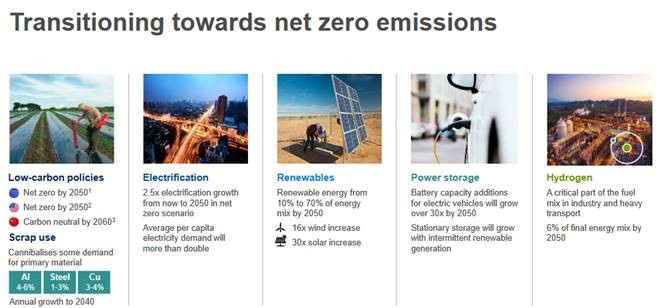

Apart from the digging involved in mining, the truth is that a cleaner world requires more metal. A LOT of it.

Cars with an electric motor consume 4x more copper than cars with a combustion engine. They’re often made of lighter aluminum, too.

Originally marginally produced metals, lithium, cobalt, and nickel nowadays play a key role in batteries. Renewable energy production is no different. A solar panel requires silver, a windmill requires tons of steel made of iron, and hydrogen fuel cells require platinum or palladium. Both rare earth minerals and gold are necessary for robotics and smart grids.

The demand for metals is bound to increase if we want to combat climate change and modernize our energy infrastructure. For this reason, mining is the lesser of two evils compared to fossil fuels.

The financial world is slowly catching on, with talk of a “commodities supercycle” making headlines.

Source: www.thestreet.com

Source: www.economist.com

Picking the right target

As the economy changed, it was vital to focus on the right commodities. Coal mines may be on the way to becoming stranded assets, with a negative value. As a result of the ethical and legal issues discussed above, I also wanted a company based in the West and required to conform to high standards.

Copper and lithium seem like smart picks for a market where electrification is an unstoppable trend (even if it’s slower than we would wish).

Iron is also a metal that isn’t going out of style anytime soon. This is due to its use as a building material for everything from bridges to skyscrapers, windmills to aircraft carriers. The use of aluminum could also be a viable alternative to copper given that it is increasingly used in the automotive industry.

Finally, being the value investor that I am, I wanted a company that offered a large margin of safety at a low price. Better still, if it was highly profitable, well managed, and had efficient capital allocation. With today’s technology-obsessed marketplace, there is an overabundance of choice. Most large miners are undervalued at the moment.

Therefore, I decided to do a double report that presented two companies simultaneously, each with different opportunities and risks. By doing so, you can choose what is most appropriate for your portfolio.

My attention was immediately drawn to Rio Tinto, the world’s third largest mining company. This company is trading at an absurdly low price, has a diversified portfolio, and trades at a criminally low P/E and P/FCF multiple. Upon investigating the company, I learned it had recently struggled with bad news that scared away investors. The market overreacted to the news and has now absorbed more than its share of the risk. But more on that later.

For the second company, it was a virtual tie between Lundmin Mining and Fortescue Metal. Fortescue won as a result of a lower price and a higher dividend yield.

In the report’s introduction, you will find the key metrics for Fortescue and Rio Tinto. I am sure many other mining companies could also have been a wise pick, since the entire sector appears to be on sale.

Chapter 2: The metal business

The metal mix

Prior to looking into the price and valuation of these mining giants, I wanted to understand each company’s business.

Fortescue Metals

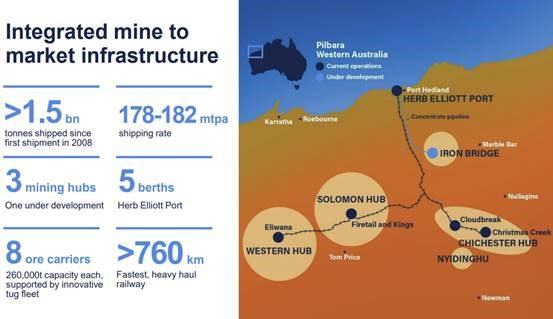

Fortescue is by far the easiest to understand of the two. It is the 4th largest iron ore producer in the world, producing only iron.

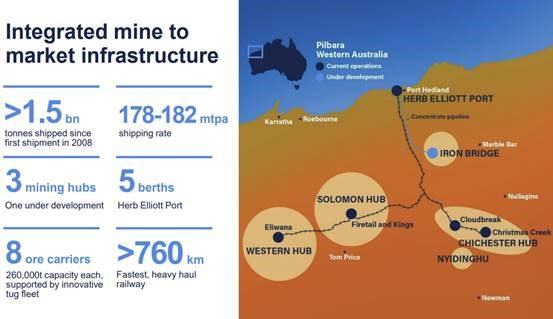

In the Pilbara region, Fortescue operates exclusively (the neighboring mines are notably owned by Rio Tinto). With a strong rule of law and high-quality metal deposits, the country is one of the world’s best mining jurisdictions.

For exporting its iron to Asian markets, especially China, the company operates its own heavy-duty railroads and key infrastructures at the local harbor.

Fortescue has no plans to significantly expand in other metals or in other countries. Instead, it plans to expand its Pilbara operations.

In the following chapter, I’ll discuss the companies ambitions to expand into green hydrogen production.

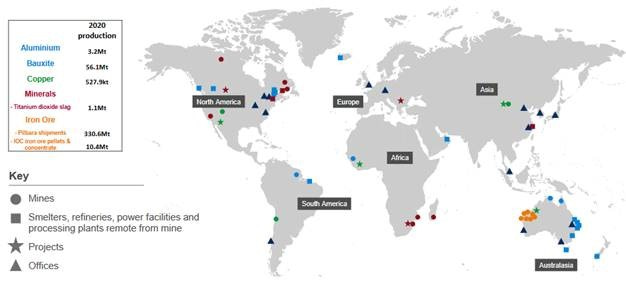

Rio Tinto

Rio Tinto is one of the world’s largest mining companies (the third largest) and has a much more diverse profile than Fortescue. Their operations span the globe. I won’t go into detail about each, otherwise this report would sprawl to hundreds of pages.

Let me instead give you an overview of the company as a whole, and then review the company’s most significant and largest growth projects.

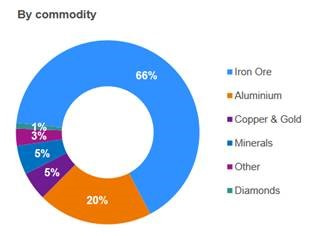

Source: RT Fact Book

Iron ore and aluminum dominate the company’s revenues, with the other metals making up less than 40% of the total.

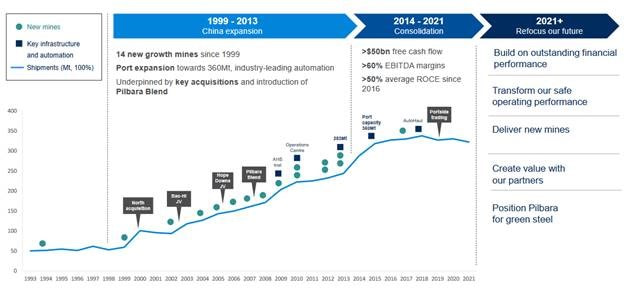

Rio Tinto operates in the same Pilbara region that Fortescue does, and has 14 iron mines in Australia. Rio Tinto’s historical iron business remains its core business to this day.

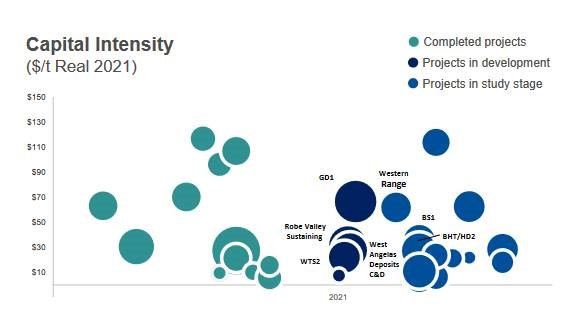

The company also plans to keep expanding its iron mining operations in the area, with multiple large new mines in the works or being studied. Interestingly, most of these mines are in the lowest cost range, an important feature of the Pilbara region’s iron deposits.

Rio Tinto also operates a fully integrated aluminum business, from bauxite ore to refineries, smelters, and even hydropower plants (notably in Iceland) to generate the required energy carbon-free. Aluminum production is an extremely energy-intensive industry, hence the requirement for 4.1 GW of power.

Rio Tinto is also protected from unstable energy prices by this integrated energy production, which should give it an edge over its competitors. As an example, Alcoa plans to shut down its Spanish plants for two years due to the ongoing European energy crisis. Others are following suit. The company will be able to offer aluminum products in the meantime.

Rio Tinto also produces copper, titanium, and diamonds.

There are several mega projects being developed by Rio Tinto, including extending its copper mine in Mongolia (which garnered a lot of bad press, but more on that later), and developing a giant lithium mine in Serbia and Argentina. As a result of these projects, Rio Tinto is in position to become a key player in the field of battery metals and electrification.

The iron market

Demand

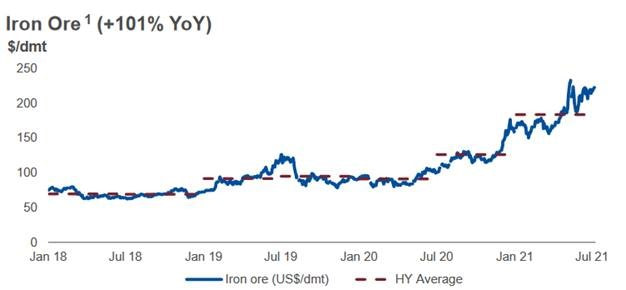

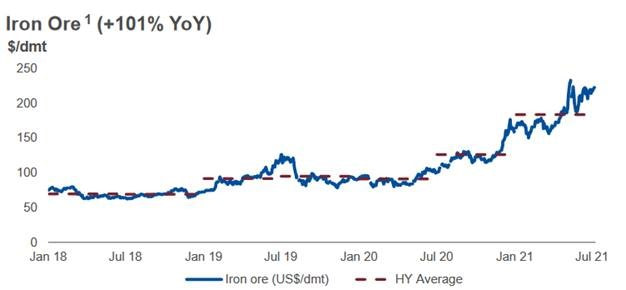

Given the importance of iron to both companies (the only one relevant to Fortescue), I had to delve deeper into iron markets. Iron ore prices have increased dramatically in recent years, from an average of $60-$70 to $200. This needs to be considered when valuing both companies. Even so, they were both profitable and doing well at the price of a few years ago, though not as massively so as they are today.

Source: www.riotinto.com

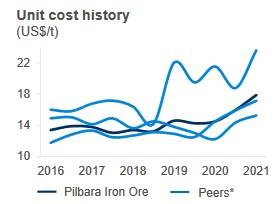

Regardless of iron market prices, the Pilbara iron unit cost is much lower than the historical average and below recent prices.

Source: www.riotinto.com

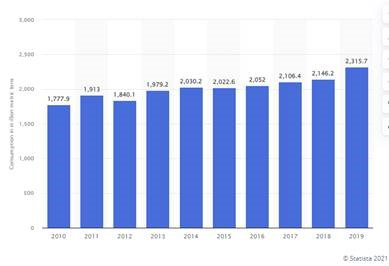

Steel is primarily made from iron. The Chinese demand for construction and infrastructure has continuously grown and accounted for a large part of this growth. As a result of Evergrande’s bankruptcy and the broader Chinese real estate market unraveling, the iron price might decline significantly.

Source: www.statista.com

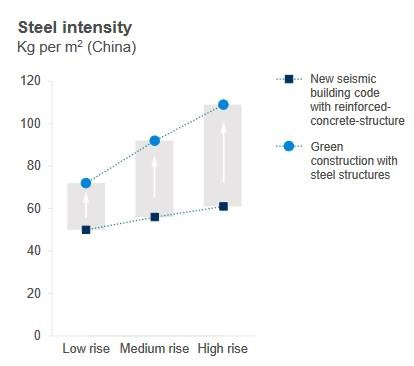

In part, this could be compensated for by better quality in the construction sector, which is well known in China for its fluctuating quality. In addition to green construction, advanced building design should also increase steel usage in new buildings.

Source: www.riotinto.com

Supply

Demand is hard to predict in commodity investing. Since mining has a very long lag between exploration, development, and starting up new mines, it is much easier to forecast near- and medium-term offers. Often, a project takes between 10 and 15 years to be completed.

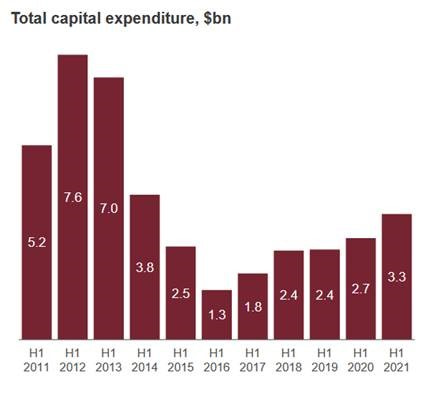

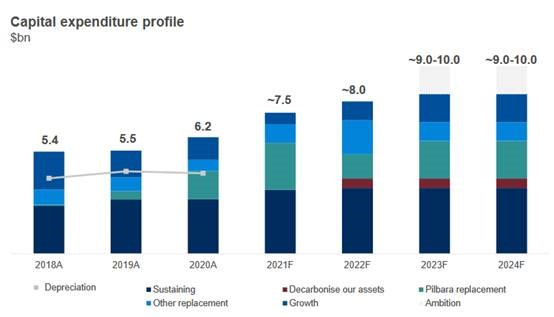

The mining industry has kept strong discipline on capital expenditure the last 5-7 years, and spending has not recovered to early 2010s levels. You can see Rio Tinto’s historical capital expenditures below. Rio Tinto is quite consistent with the rest of the industry in this regard.

As a result, new mines and supplies are unlikely to enter the market anytime soon. As long as demand doesn’t collapse completely (reaching a level comparable to the Great Depression), iron prices should remain relatively high for some time.

Source: www.riotinto.com

Other metals

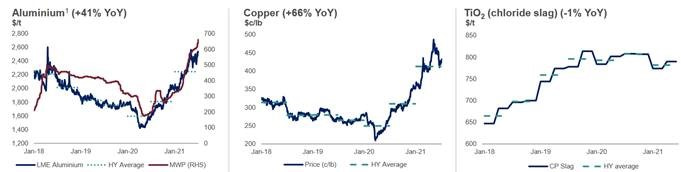

Metals other than iron also display the same profile, with a sudden and strong increase in prices in 2020 and 2021. This resulted largely from too low capex within the industry as a whole, causing the sudden shortage. Moreover, Covid-related stimuli have increased demand.

Copper and lithium demand is likely to remain high in the long run due to electrification, especially for copper.

Titanium is used primarily as a pigment in paints, but it has significant potential in manufacturing as well. Thanks to its corrosion resistance, high temperature resistance, and high pressure tolerance, it is becoming increasingly popular in aerospace and other high-tech applications.

Source: www.riotinto.com

Copper & lithium

Copper is already a large part of Rio Tinto’s offer and future plans, so let me provide a more detailed overview of the copper market. Rio Tinto’s development of the Jadar lithium mine in Serbia is also of special interest.

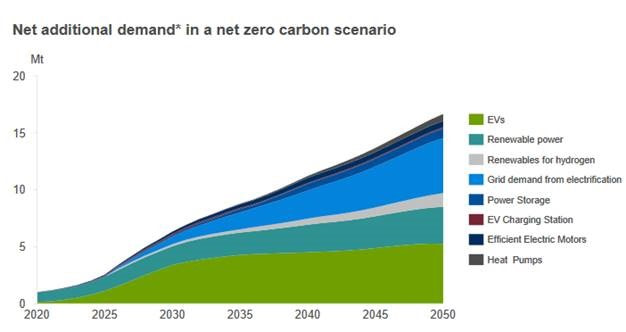

In the next three decades, the demand for copper is expected to grow by no less than 20 million tons per year, driven by the shift to electric vehicles, grid upgrades, and renewable energy. Rio Tinto only produces 500,000 tons per year, despite being one of the largest copper producers in the world. By 2050, a net-zero scenario would require 15,000,000 tons of resources!

So yeah, there’s a lot of demand.

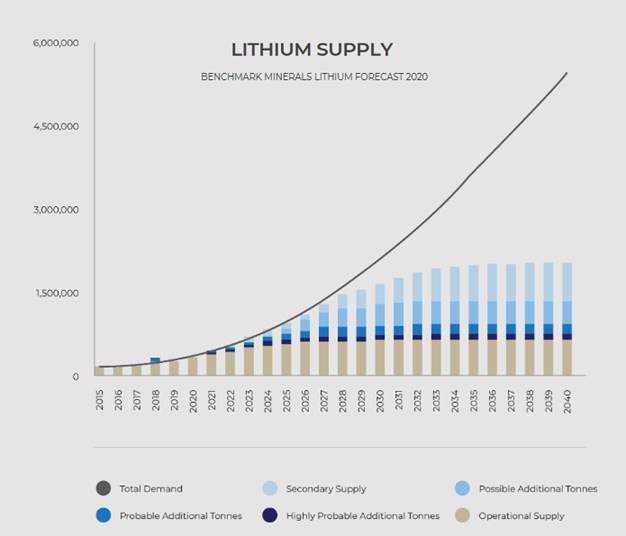

Even more dramatic are the effects of electrification on lithium. It is estimated that current mines in operation and the planned expansion will not be able to satisfy a large percentage of the demand in 2030-2040. Considering the time it takes to start a new mine, this could cause a chronic shortage of lithium and elevated prices from 2025 onward.

Source: www.rinconmining.com

Rio Tinto reserves

A crucial aspect of mining is checking reserves. Mines have a limited lifespan after which they run out of ore reserves. Therefore, every mining company has a ticker on their heads, and they will run out of metal at some point.

A miner’s reserves are usually enough to last 10-20 years at most. Most oil & gas companies have reserves of seven to ten years.

I am glad to report that Rio Tinto deposits are so vast that lifespan is not a concern. For most investors, Rio’s existing mines will still be operating when their children inherit their portfolios!

By the end of the century, the iron mines will likely still be in operation at their current depletion rate. Additionally, bauxite mines last about 40 years.

The Oyu Tolgoi copper deposit is one of the largest copper deposits in the world, yet it has the shortest lifespan at “only” a quarter century, and probably less once production ramps up.

Regardless, this means that Rio Tinto is an asset you can hold for a very long time if prices remain above production costs. Unlike Shell or Total, as well as many of the other energy majors, its current price does not reflect a problem with the reserves.

| Reserves | Current production | Lifespan | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Iron | 24,784 mt | 320 mt | 77.5 years |

| Bauxite / Aluminum | 2,077 mt | 55 mt | 37.7 years |

| Copper | 12,607 kt | 500 kt | 25.2 years |

Chapter 3: The troubled past and the bright future

Rio Tinto troubles

A copper motherload

This report has already referred to Rio Tinto’s difficulties in Mongolia with its Oyu Tolgoi mega copper mine project. Rio Tinto is mining the world’s biggest copper deposit and gold deposit.

Rio Tinto owns the mine through a complicated ownership structure. It is owned by Turquoise Hill to the tune of 66%, and the government of Mongolia to the tune of 33%. Rio Tinto owns 50.8% of Turquoise Hill, and therefore owns 34% of the Oyu Tolgoi mine.

Rio Tinto has produced 150,000 tons of copper and 61,800 ounces of gold as well as 300,000 ounces of silver from the open-pit mine. All is well so far.

The struggle with the Mongolian government

Things started to take a sour turn with Mongolia in 2018, with a $155M tax bill and the arrest of officials involved in signing agreements with Rio Tinto.

Things got worse, with the underground extension of the mine being delayed by 30 months and costing $1.9 billion more than expected. Rio Tinto’s management has been criticized in independent reports, and the Mongolian government began to lose patience with the company.

During the majority of 2020 and 2021, Oyu Tolgoi has been the source of alarming headlines on www.mining.com, and the share price has reflected this negative publicity. In addition, Oyu Tolgoi appeared to be more significant to Rio Tinto than it actually is.

Turquoise Hill’s debt was also a point of contention between the company and Mongolia. Turquoise Hill owes a lot of money to its parent company Rio Tinto and would not be able to pay a dividend until the debt was fully repaid. It meant that Mongolia’s government wouldn’t see any profits from Turquoise for years to come.

Considering how poor a country Mongolia is, Oyu Tolgoi, once expanded underground, should represent as much as 30% of the whole country’s GDP. Hence, political pressure on the government to obtain cash before 2041 was enormous.

In my opinion, 2041 was an absurd timeframe. The result is that Rio Tinto tried way too hard to negotiate with Mongolia and ended up risking a full expropriation as a result.

A light at the end of the tunnel

As a result of Mongolia’s rich but unexplored underground, its government has no interest in tarnishing its image as a top mining destination. Despite the short-term gains, Turquoise Hill would have lost much more if it were nationalized. This country desperately needs foreign investment.

In recent weeks, Rio Tinto offered to cancel Turquoise Hill’s $2.3B debt. In addition, it will cover the cost of the underground extension of Oyu Tolgoi, which should be completed in 2023.

Rio Tinto was forced to accept a fairer deal by the Mongolian government, on the surface a defeat for the mining giant. Personally, I see it as an excellent outcome.

In addition, it almost eliminates the possibility of a full expropriation, which is always possible in countries with weak rule of law.

The second lesson is that Rio Tinto management needs to learn that exploitative and abusive deals have negative consequences over time. Tricks like loading Turquoise Hill with debt to keep dividends away do not pay off. Even in a poor country like Mongolia. Consequently, long-term investors should be less likely to experience similar problems in the future. As a result, the company would not need to post defensive statements online ever again, as they did with Oyu Tolgoi…

Rio Tinto other mega-projects

While Rio Tinto focuses on Mongolia, its other projects and its growing profitability have been overshadowed. The other flagship project, Jadar in Serbia, is also facing opposition from investors.

Jadar, Serbia’s lithium

With a planned annual production of 55,000 tons of battery-grade lithium carbonate, Jadar is Rio Tinto’s flagship entry into the lithium market. It will also produce 160,000 tons of boric acid each year.

In the current market, this would put the project a bit below the 5th largest lithium producer, SQM (which produces 70,000 tons annually). As a side note, Rio Tinto attempted to acquire a $5B stake in SQM in 2018, demonstrating the company’s commitment to expanding into the lithium market.

Jadar’s lithium reserves are huge, and the mine should be able to operate for at least 40 years. Additionally, the deposit is of high quality, with costs expected to be in the bottom 25% of the industry (both for lithium and boric acid).

At present, most of the world’s lithium is mined in South America and Australia. Therefore, its location in Europe is also advantageous, as the region is aggressively ramping up its efforts in electric vehicle manufacturing and is looking for local suppliers.

So what is the problem with Jadar? Mostly local opposition from nearby residents. Local municipalities have canceled plans to assign land to the mine, and thousands of protesters have rallied against it. The Serbian parliament has also abandoned some reforms that would have made the country more miner-friendly after nationwide protests.

Protests like these are not unique to Rio Tinto. Most ecological activists worldwide oppose the opening of any lithium mine, or any new mine of any kind for that matter.

It seems a touch paradoxical when the same activists want to phase out fossil fuels and switch to electric vehicles instead. These changes are anticipated to consume a great deal of copper, lithium, and other metals.

Serbian protests may have a negative impact on the Jadar mine, but it is too early to tell. Nonetheless, given that lithium is in short supply, and that a lot of more is needed to manage the green transition, pressure for approving the mine should grow. Serbia is also experiencing poor economic conditions, and the project’s income and tax revenue are likely to be required by both the local and national tax authorities.

The project was to begin construction in early 2022 and last four years. In general, I expect delays and additional drama, but I still expect the mine to go ahead. Serbia will need to increase its tax revenues in order to increase lithium supply in Europe. A production start in 2027 or even 2028 is more likely than 2026, but it should happen eventually. Mining is in any case a long-term game, where “new product launch” means waiting for 5-7 years. As part of its long-term strategy, Rio Tinto also invested in Slovakia-based battery manufacturer InoBat Auto.

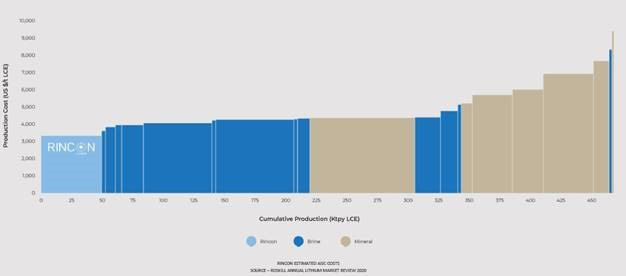

Rincon Mining, Argentina’s lithium

Acquisitions, on the other hand, are more of a surprise to shareholders. New mines are easy to forecast years before production begins, but acquisitions are less predictable. In order not to tip off competitors and start a bidding war, management often keeps them secret. This was the case with the acquisition of Rincon Mining for $825M.

The company’s website says the mine should be the world’s lowest-cost manufacturer. The region is also expected to have one of the lowest carbon footprints in the world due to its reliance on renewable energy sources (including hydropower in the region).

The plant should have a production capacity of 50,000 tons/year for 40 years. In addition to Jadar, this would catapult Rio Tinto into the top 3-5 lithium producers in the world.

A small test plant should be up and running by 2023, and a 50k/year plant by 2026. About the same time the Jadar mine is set to start up.

In addition to becoming a large lithium producer, Rio Tinto will also have some of the lowest production costs in the market and 40+ years of lithium reserves.

Simandou, Guinea’s iron

Rio Tinto is developing a large and higher grade iron deposit in Guinea called Simandou. It won’t be as cheap as Pilbara ($35-$40/ton compared to $15-$25/ton), but still well below 2019 prices.

Source: www.riotinto.com

Rio Tinto owns 45% of the project. The mining rights have been held by Rio Tinto since 1997. Up until higher prices and the Chinese government’s interest in more supplies pushed the company to develop more iron mining, the company was not eager to do so.

With iron ore prices now 4x higher than Simandou production costs, Rio Tinto has a solid margin of safety to launch the project. This is an extreme case of long-term capital planning.

Fortescue growth plans

Iron production growth

Fortescue produced 176 tons of iron last year and plans to increase production to 220-230 tons per year as it expands its existing mines and develops the new Iron Bridge mine.

The company has managed to keep production costs at an astonishingly low $13/ton. It is so low compared to the existing market price that even a massive drop in iron demand would not make the company unprofitable.

Dig it for $13 and sell it for $100-$200. Simple as that. Moreover, the company has reserves of at least three decades, so it can stay in business for a long time to come.

Other metals?

Fortescue’s annual report mentions in passing some copper and lithium exploration projects in South America and Kazakhstan, but doesn’t provide any details. As they stand, I would not consider them of any value to the company, and I would keep them as an unknown potential for the very long term.

Green hydrogen lofty plans

Fortescue seems to be the least interesting of the two companies in this report at first glance. It focuses on one metal and one region in one country. You dig it for a low price, sell it for a high price, and pocket the difference.

Both Fortescue and Rio Tinto are putting considerable effort into communicating how green their operations are. This includes using electric trucks and using solar panels for electricity. All of these initiatives are worthwhile, but they are more token ESG efforts than core business initiatives.

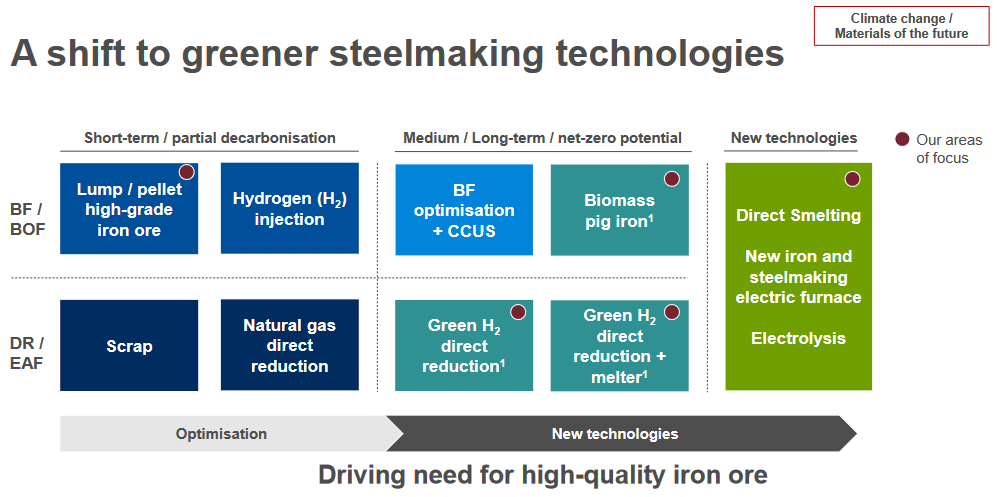

Perhaps pure greenwashing, it’s difficult to tell. See the slide below from Rio Tinto as an example. Good efforts, but they won’t change the core of Rio Tinto’s operations:

In the beginning, I thought Fortescue’s comments about focusing on hydrogen generation as the future of the company were also just ESG distractions/greenwashing.

Upon further examination, it appears that the company’s management is serious about it. I considered this to be a serious threat to the company’s future. Fortescue has experience handling mining equipment, not energy infrastructure. In spite of the fact that mining and utilities handle some heavy machinery in common, they are very different industries. I feared that it would distract the company and waste a great deal of cash.

Furthermore, I am not optimistic about the prospect of hydrogen as a fuel in general. I won’t go into too much detail, but hydrogen is just energy storage, not really a fuel. Hydrogen must be produced from electricity, and this electricity must also be green in order for the hydrogen to be environmentally friendly.

This process of hydrogen generation, liquefaction, storage, and transportation wastes a great deal of electricity. In almost all use cases, it is better to use this electricity directly rather than making hydrogen from it.

Hydrogen is a perfect match for an iron miner

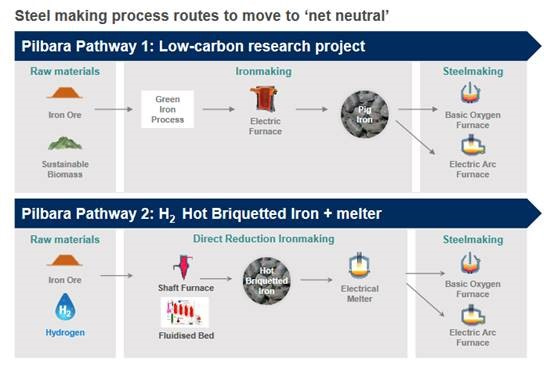

Only after reading Fortescue’s explanation did I understand why they were interested in hydrogen. The solution is not, as I first thought, to become a hydrogen producer and export it overseas. It can also be used locally for transportation. Instead, it is intended to capture more of the iron ore value chain.

Prior to being used to make steel, iron ore must first be purified. Throughout the industrial era, coking coal has been used in this process. There is no substitute for this type of coal in the production of steel. Thus, steel production is a very carbon-intensive industry, and it is difficult to avoid such emissions.

Or so I thought.

In the past, only “low carbon” options were considered. This meant using “sustainable biomass” instead of coking coal. Most likely, biomass here meant a lot of wood. It might have been very large forests that were burned. The act of burning might have been carbon-neutral, but not so environmentally friendly.

Recent innovations have allowed iron ore to be purified without burning coal by using hydrogen instead. This has quickly evolved from a theoretical possibility to a rush to upgrade iron smelters across Europe. In fact, the first deliveries of this “hydrogen steel” to carmakers were made last summer.

Fortescue’s focus on hydrogen is not a distraction or a diversification out of Fortescue’s area of competence, as I had thought. The problem has nothing to do with hydrogen, but with iron, which Fortescue knows very well.

In the future, instead of shipping iron ore as it does today, the company will perform the ore reduction process. This will enable it to capture more of the value chain along the way. Getting green energy in the outback of Australia will be easier due to its dry climate and sunshine.

Whether this activity will be profitable is something I am unsure of. At the very least, it will not produce a loss. Additionally, it will produce goodwill and carbon credits for the company.

The most likely place for hydrogen in the energy mix is in steel production. And if I am wrong about hydrogen’s other uses, Fortescue will have a good chance of selling green hydrogen to foreign countries as well.

Chapter 4: Financials

I am fairly satisfied with both companies’ reserves and outlook. Each is also positioned in metals that are in demand and will continue to be in high demand for decades to come.

Additionally, both are trading at very low valuations. This may be due to the fact that the entire commodity sector is somewhat discounted. To be sure, I needed to check the companies’ financial statements. There may be other problems contributing to the apparent cheap price, such as high debt, poor cash flow, or other factors.

Fortescue

Fortescue saw revenue rise from $12.8 billion in 2020 to $22 billion in 2021. This translates into very large earnings of $10 billion.

For such a capital-intensive business, the debt is low, reflecting management’s prudence. In addition, most of the debt is due in 2027 and 2031, and at rates that are below the current inflation rate (4.3%-5.1%). Finally, the mining industry appears to be learning how to manage the price cycle better and pay off debt at the right time.

With $6.9B in cash and $10.6 in total liabilities, the balance sheet is solid. There is no net-net, but it’s not bad.

The cash flow from operations stands at $12.6B, while $3.6B was spent on maintenance and growth capital expenditures. In total, cash increased by $2B, with dividends paid to shareholders adding $5.6B to the amount.

Therefore, even while repaying debt and investing in growth, the company could cover the very large dividends. Dividend yield is 18.2%, which is insane!

Overall, all indicators are flashing green.

As long as there is no worldwide recession, they should be fine. This can be said of almost any company, so I will not hold it against Fortescue. Fortescue’s low multiples, as well as its high dividend yield, should provide some safety compared with overvalued and popular stocks.

Fortescue’s largest client is by far China, accounting for $20B of its $22B revenue. China’s demand might slow down in the wake of Evegrande’s bankruptcy, which would threaten the company’s cash flow.

The very low debt and the very low production costs make me wonder what could actually threaten the company. At worst, the company could mothball some mines and weather a storm comfortably, even with reduced cash flow.

Rio Tinto

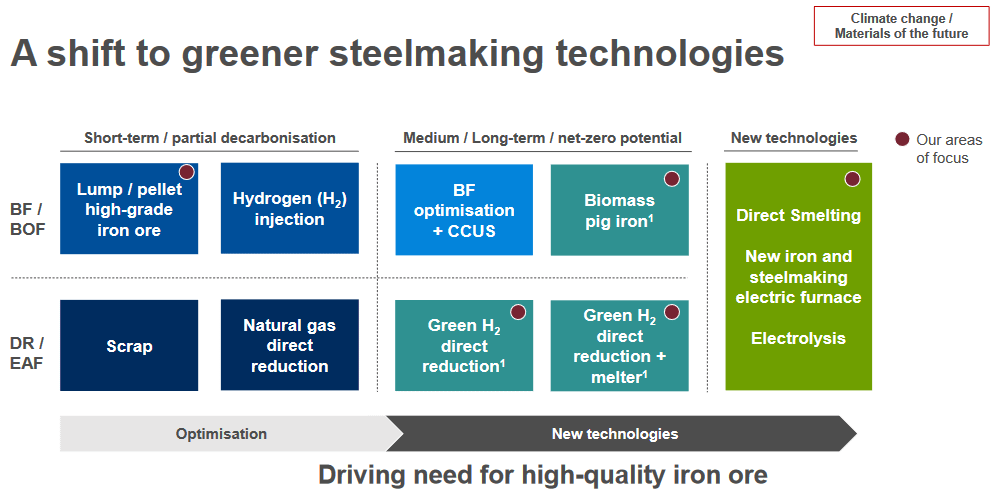

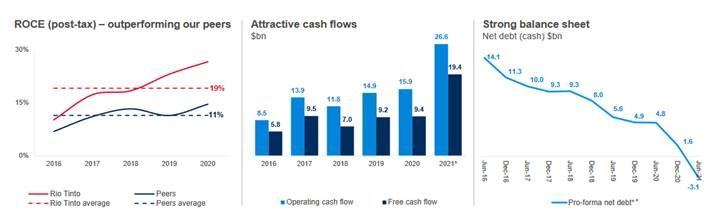

Rio Tinto’s financials look a lot like Fortescue’s. As of 2021, the company has negative net debt (down from $14B in 2016), massive cash flows, and an extraordinarily high return on capital.

Free cash flow of $19.4 billion was partially used to pay dividends of $9.1 billion, for a dividend yield of 10.2%. Current metal prices cover the dividends very well. The company typically distributes 40%-60% of earnings as dividends, and more during times of strong earnings.

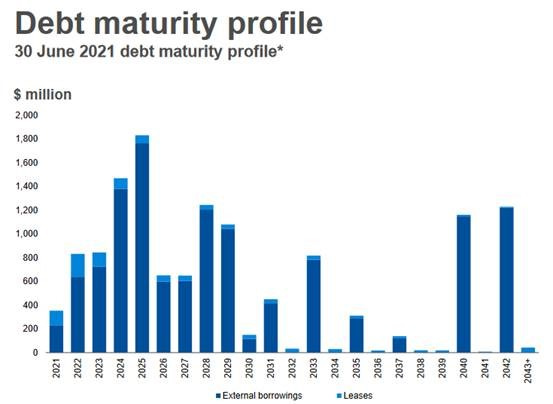

The rest of the cash flow was used to cover capital expenditures and debt repayments. The long-term debt of Rio Tinto now stands at $13.4B. Rio Tinto’s balance sheet is less pristine than Fortescue’s, but still very strong. Most debt maturity is relatively soon (for a miner) in 2023-2025, and probably should be pushed forward sooner than later.

Additionally, cash flow was used to add to a large $12.9B cash treasure chest. I expect some of the treasure chest to be used for more aggressive acquisitions of smaller lithium and copper mining companies.

In contrast to Fortescue, Rio Tinto is planning aggressive growth with its mega projects in Mongolia, Guinea, and Serbia. Part of this explains why it focused on growth instead of solely paying off its debt.

It is pertinent to keep an eye on the capital expenditures forecast and see how much free cash flow it will absorb with so many new mines coming online.

As compared to 2021, capex should increase by $3B to $4B in 2024. This is barely going to affect the company’s free cash flow, which is expected to stand at $19.4B in 2021.

Moreover, this could even have been covered by the 2016 free cash flows, a period of low commodity prices. Cash on the balance sheet could also cover the extra capex for the next three years.

Rio Tinto’s other concern is the impact of the multiple issues it has with local governments and ecologists. To renegotiate its deal with the Mongolian government, the company had to fork over $2.3B.

Even though this is not much, the company still had $9B in free cash flow after dividends. It is unlikely that Jadar in Serbia would incur the same extra costs (for example, more stringent environmental regulations).

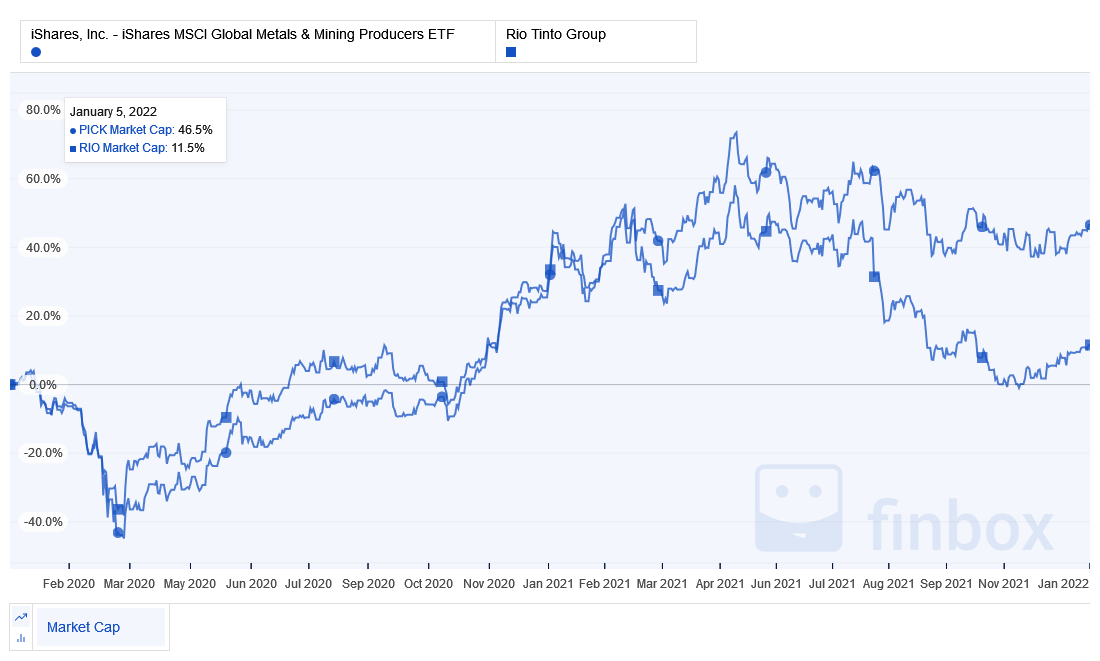

Is it fair to say that Rio Tinto’s stock barely gained anything in the last 2 years (+11% in 2 years)? Especially when the general commodities ETF spiked by 46%? I don’t think so.

Investors tend to overreact to bad news, which provides value investors with lucrative entry points. Rio Tinto’s margins are exploding, their balance sheet is strengthening, but their stock price is declining.

Chapter 5: Valuation

My standard calculation for miners would have been to consider the total value of the ore until depletion. In the past, I valued Kirkland Lake like that. With Rio Tinto and Fortescue both having mine lifespans in the range of three to seven decades, I will do a simple discounted cash flow calculation.

Discounted Cash Flow

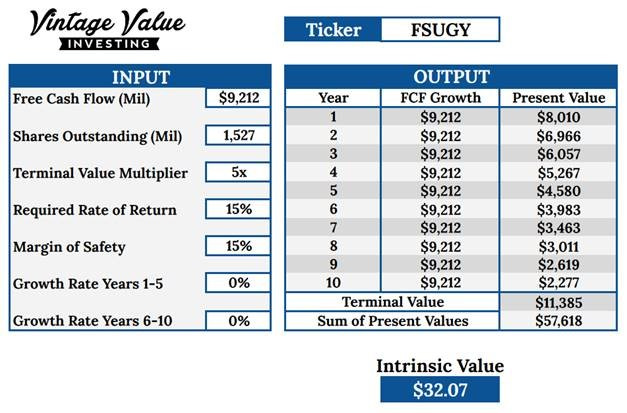

Fortescue

Historically, the price to free cash flow ratio has been very unstable. I’ll pick a lower level of 5 to remain (very) conservative.

With extra production and higher ore prices, free cash flow could continue to grow. Conversely, a slowing Chinese economy could kill growth. First, I wanted to run the valuation with 0 growth and see what the results would be.

With these conservative assumptions, Fortescue Metals would be valued at $32, slightly above its current stociank price of $28.91.

A return of 15% seems quite safe, even if multiples never climb back up (unlikely, considering the historical volatility) and cash flow does not increase in the next decade.

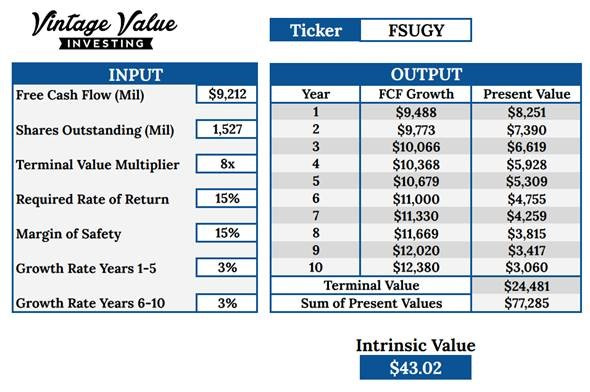

Had I wanted to give a more optimistic outlook, it would not have been difficult. With just 3% growth and a slightly higher multiple, the company would be 1/3 under its intrinsic value.

In the end, I decided to opt for the worst-case scenario. Despite growth in production, cash flow has been permanently reduced (despite multiple contractions). Returns at the current price would still be around 10%.

DCF calculation illustrates perfectly the importance of margin of safety. In the absence of a major recession or depression, it is difficult to lose money on undervalued assets that are generating cash flow.

Last but not least, these numbers do not include any potential success in the green hydrogen and green iron ore/steel sectors. Thus, the potential for upside is even more significant.

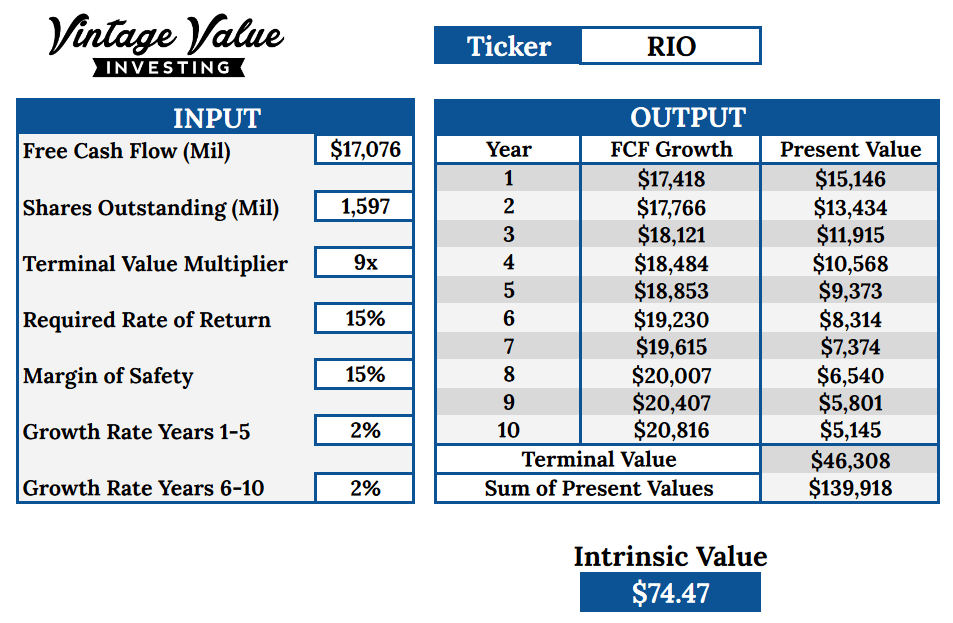

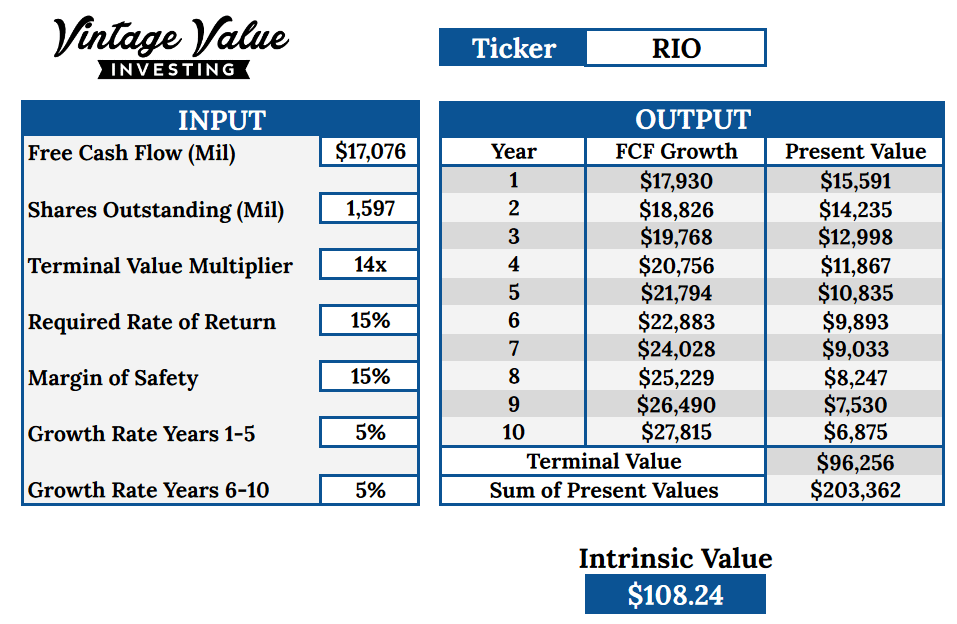

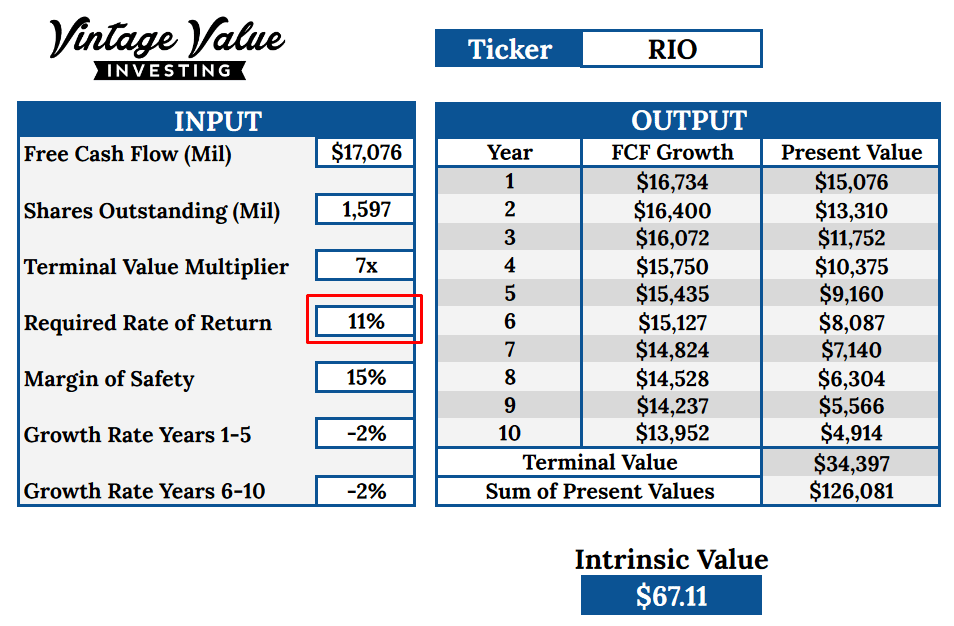

Rio Tinto

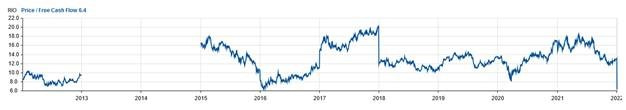

Price to free cash flow ratios have historically been very unstable here as well. In general, it appears that markets have rewarded Rio Tinto’s more diversified assets and its sheer size over Fortescue’s. I will choose the lower level of 9.

If the Chinese or global economy slows down, then free cash flow may also stagnate. However, with so many mega projects already in the pipeline, some growth still seems reasonable.

Despite these conservative assumptions, I have a value for Rio Tinto Group of $74, slightly above the current $67.52

Rio Tinto’s 15% return also seems safe, even with multiples never returning (unlikely considering the historical instability) and cash flow barely increasing in the next 10 years.

Likewise, I will run optimistic and pessimistic scenarios for Rio Tinto. In the optimistic case, I get a company 1/3 below its intrinsic value, and in the pessimistic case, I get 11% returns.

I was surprised to see that both companies had such similar profiles, since I assumed Rio Tinto would offer better returns. I might be underestimating Rio Tinto’s growth, but anything higher than 5% a year seems unrealistic in a capital-intensive industry.

In this calculation, I only considered the current business conditions. The cash flow for Rio Tinto would completely explode beyond 2026 if a chronic shortage of lithium and/or copper occurs due to green policies. In this case as well, the upside potential is greater than the downside potential.

Conclusion

With the current cash flow and depressed valuation, both companies would be smart picks with a large margin of safety. As commodity traders, they will be sensitive to macroeconomic conditions:

- If inflation remains high, they will outperform and may become the next market darlings instead of tech. Mining companies are in an ideal situation under this scenario.

- If the global economy suffers a recession, and especially if the said recession is severe in China, the two companies would suffer. Their current large cash flow would shrink dramatically to 2015-2016 levels at least. Although the current multiple is low and the balance sheet is solid, the losses should be contained at an acceptable level. The miners of 2022 are not the debt-ridden miners of 2015.

Now, how should they be incorporated into a portfolio?

It depends on what your investment goal is. Is your goal to reduce volatility and be protected from inflation risks, or are you looking to maximize returns? Maybe you want exposure to the green transition without having to guess what technology will win?

A small allocation of 5-10% of the portfolio for inflation risk seems reasonable. Additionally, a 50-50 split between the two miners would provide some diversification.

To maximize returns, a higher allocation of 10-20% would be ideal. Fortescue offers a higher dividend yield and generally lower risk. However, in the case of persistently high prices, it will not be able to reap the benefits for at least 6-10 years (the time it takes to launch new mega mines).

If metal prices continue to rise, Rio Tinto will generate better returns due to its aggressive profile. It is also more vulnerable to recessions due to its more ambitious expansion and greater debt.

I expect both companies to provide similar returns in the long run, though Rio Tinto may perform slightly better. Compared to Rio Tinto, Fortescue will be less volatile and less prone to price fluctuations, scandals, and protests.

In order to gain exposure to the electrification trend, Rio Tinto is a smart choice. In addition to aggressive expansion of its lithium business, it will continue to grow its copper production. The hydrogen bet could also pay off for Fortescue, but it is unlikely to provide the same level of benefits as Rio Tinto’s multi-country mega-projects.

Some investors have multiple goals at once and prefer a different mix for their portfolio. Therefore, it depends on your tolerance for volatility, your time horizon, and the composition of your portfolio.

The tech-driven rally is showing increasing signs of speculation and instability, so I think it is time to bet again on “real atoms” versus “virtual bits.”

Personally, I would like to keep a part of my portfolio in a safe harbor with these two undervalued miners, along with some energy and gold as well.

Holdings Disclosure

Neither I nor anyone else associated with this website has a position in RIO nor FSUGY and no plans to initiate any positions within the 72 hours of this publication.

I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own personal views and opinions. I am not receiving compensation, nor do I have a business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

Legal Disclaimer

None of the writers or contributors of FinMasters are registered investment advisors, brokers/dealers, securities brokers, or financial planners. This article is being provided for informational and educational purposes only and on the condition that it will not form a primary basis for any investment decision.

The views about companies and their securities expressed in this article reflect the personal opinions of the individual analyst. They do not represent the opinions of Vertigo Studio SA (publishers of FinMasters) on whether to buy, sell or hold shares of any particular stock.

None of the information in our articles is intended as investment advice, as an offer or solicitation of an offer to buy or sell, or as a recommendation, endorsement, or sponsorship of any security, company, or fund. The information is general in nature and is not specific to you.

Vertigo Studio SA is not responsible and cannot be held liable for any investment decision made by you. Before using any article’s information to make an investment decision, you should seek the advice of a qualified and registered securities professional and undertake your own due diligence.

We did not receive compensation from any companies whose stock is mentioned here. No part of the writer’s compensation was, is, or will be directly or indirectly, related to the specific recommendations or views expressed in this article.