In his 2020 book, “The Psychology of Money,” Morgan Housel makes an observation that we all understand on an intuitive level but still have a hard time accepting:

Doing well with money has little to do with how smart you are and a lot with how you behave. And, behavior is hard to teach, even to really smart people. A genius who loses control of their emotions can be a financial disaster.

The opposite is also true. Ordinary folks with no financial education can be wealthy if they have a handful of behavioral skills that have nothing to do with formal measures of intelligence.

The problem with this statement is that we all want to believe that financial success is always a result of brains and hard work. It can be hard to believe that numerous psychological factors influence our financial decisions, especially when we believe we are smart.

After all, not only are we smart, but we also know ourselves so well that we’ll quickly spot any cognitive bias that tries to sway us, right?

The Problem With Being Smart

While we can solve countless problems with nothing but our wits, we can’t outmaneuver our cognitive biases. If anything, the smarter an individual is, the more likely they are to be tricked by their subconscious without even realizing it.

🧠 A study published by the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology argued that smarter people may be more likely to commit thinking errors than the everyday Joe.

Why are Smarter People More Susceptible to Cognitive Biases?

There are a few reasons:

Confidence Can Be Misleading

According to Nobel Prize-winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman, our confidence in a proposition has more to do with how cohesive it is with everything else we know than anything else. More accurately, Kahneman puts it as follows in his seminal work, “Thinking Fast and Slow”:

Confidence is a feeling, which reflects the coherence of the information and the cognitive ease of processing it. It is wise to take admissions of uncertainty seriously, but declarations of high confidence mainly tell you that an individual has constructed a coherent story in his mind, not necessarily that the story is true.

And who’s better at coming up with a coherent story than smart people?

A smart person will often act without realizing their subconscious is behind the wheel. Afterward, they will rationalize their actions post hoc, and their explanations will be so eloquent and convincing that it would be almost impossible to decide whether a cognitive bias had played any part at all.

The Blind Spot Bias

The blind spot says that we are much better at noticing cognitive biases in others than we are at noticing them in ourselves.

So, when someone else makes a bad decision, it is clearly due to how they were using faulty logic, weren’t lucid enough at the time, and were just plain wrong.

But, when we make a bad decision, it is due to having bad information, having a lot of stress to deal with, and not having enough time to consider all the factors at play.

Because of the blind spot bias, almost everyone believes that they are less biased than their peers, but none more so than smart people.

There Are Too Many Cognitive Biases Lurking In These Waters

In addition to the blind spot bias, there are countless other cognitive biases we all have to contend with (more than 180 have been documented). Even if you are on the lookout for a specific bias, hoping to avoid it, this won’t stop the remaining 179 from tripping you up.

It is easy for smart people to become victims of cognitive biases. For starters, they are better at seeing the faults in others than in themselves, making them feel superior to those around them and immune to biases. When they do make a mistake, they can conjure up a coherent story, one completely devoid of any errors in thought on their part.

And, to top it all off, every one of us has to contend with numerous biases lurking at every corner, waiting for us at every fork in the road.

However, most of us don’t need 180 cognitive biases to trip us up. Some biases are so pervasive that they show up over and over again every time we make a big decision.

Loss Aversion

When talking about biases that cut across almost every facet of our financial decision-making, there is no better example than loss aversion.

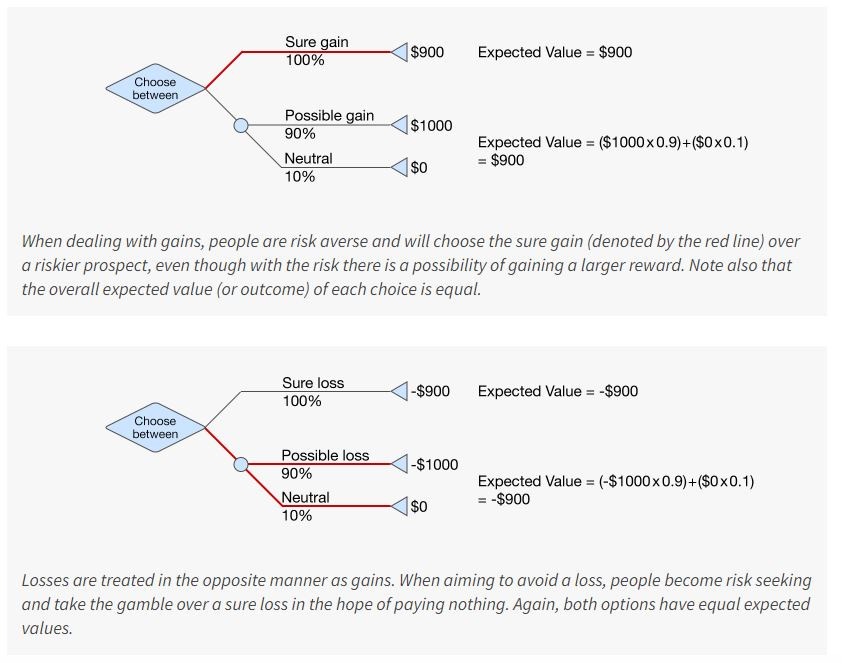

According to this principle, the pain of a loss is up to twice as intense as the pleasure of a win.

👉 For Example

Try going out and offering a random stranger the following game:

You will both flip a coin once and only once. Heads, they pay you $100. Tails, you will pay them $200. What you will find is that most people wouldn’t take you up on that offer even though, from a completely rational standpoint, you are giving away money.

And that is the main problem with loss aversion. It makes us act irrationally in all areas related to risk and money. Loss aversion is one of the main biases that Daniel Kahneman feels every investor should know.

Armed with that knowledge, let’s see how loss aversion can wreak havoc with our finances, especially when it shows up disguised in different forms or comes paired with other biases.

The Psychological Factors Influencing Our Personal Finance Decisions

Personal finance can be broken down into the following five areas:

- Income includes your salary, bonuses, and the dividends from your investments.

- Spending covers your expenditures.

- Saving covers money that you make but choose not to spend.

- Investing covers money you place in instruments you believe will increase in value over the long term.

- Protection includes any financial product you buy to protect yourself from future risks.

Let’s explore how cognitive biases can influence each area.

1. Income

Your income is any form of money you get and can spend. This money might come about thanks to your job, your investments, your end-of-the-year bonus, or any other source.

However, on the path to earning your income, you are liable to make a few errors in judgment without ever realizing it.

Familiarity Bias

We all prefer the devil we know over the one we don’t, and nowhere is this more apparent than when it comes to our jobs.

And this is where the familiarity bias comes into play. It dictates that we tend to believe that the things we are most familiar with are more valuable than the things that are foreign to us.

For example, if someone came to me and told me about a different but better way to do my job, using a different process perhaps, odds are my initial reaction will be to dismiss said individual along with their suggestion. Without a good enough reason, I will most likely feel comfortable sticking to what already works, even if it isn’t the most efficient way of getting things done.

There’s a good reason we tend to stick with what is familiar: We have confidence in it. We know that the chances of failure and loss are much less with what we know compared to what we don’t know.

However, when it comes to our careers, sticking to what works is not a sustainable strategy. We need to change, grow, and grapple with the unfamiliar and unknown. Otherwise, we risk going the way of the dinosaurs.

Comparing Ourselves to Others

Even though this one isn’t exactly a cognitive bias, it is still very relevant to our conversation. So, it had to make its way to our list.

According to a paper by the social psychologists Gao, Sun, Du, and Lv, our happiness with our careers is affected by social comparison.

👉 For Example

For instance, imagine asking a random group of people which of the following two scenarios they would prefer:

- Scenario A: They will make $200k a year while living in a neighborhood where everybody else makes $300k a year.

- Scenario B: They will make $100k a year while living in a neighborhood where everybody else makes $60k a year.

Which of the two scenarios do you think most people would choose?

The surprising answer is that most people would go for scenario B although they will be making less money in absolute terms. They will succumb to their instinct to outperform their neighbors rather than act rationally and go for the job that brings in the most income.

Admittedly, it is hard to remember that the ultimate race is always with yourself. So long as you are doing better today than you were yesterday, then you are taking positive strides toward a better life.

2. Spending

When you receive your income, the first thing you probably do is spend a portion of it on everyday necessities: rent, bills, and groceries, to name a few. Now, you might want to believe that all of your expenditures are justifiable, but you would be surprised at how biases can skew your judgment.

Framing

How information is presented to you can have a huge impact on your decision. This is known as the framing effect.

⚕️ To see this effect in action, take a look at the following two examples:

- You’re considering a medical operation that has a 95% chance of success.

- You’re considering a medical operation that has a 5% chance of failure.

If you were to ask people to choose between those two options, a lot more would go for the first option over the second, even though those two options are identical.

The only difference between the above two scenarios is how they were framed. Option (a) focused on the possible success of the operation, while option (b) focused on its possible failure. That shift in perspective makes all the difference.

🦷️ While the above example was a bit extreme, the framing effect impacts your spending decisions every day, and marketers know it. You buy toothpaste that is recommended by 4 out of 5 dentists, you opt for detergents that kill 99.9% of germs, and you eat yogurt that is 80% fat-free.

As a result, we are liable to make poor decisions just because they looked attractive at the time, thanks to positive framing.

The Messenger Effect

Speaking of marketers and their wily tricks, have you ever noticed how marketers will try and sell you a product through some type of influencer marketing/ celebrity endorsement?

This is the messenger effect in action.

Simply, the messenger effect is when you believe something because you like the person telling it to you. For instance, I am a big Tom Hanks fan, so when he endorses a certain product, I am more likely to be influenced than if another actor I don’t like were to endorse the same product.

More importantly, the messenger effect is strongest when we perceive the person delivering the message as an authority figure, i.e. someone who knows right from wrong and can ensure that we avoid a loss.

But, because I am aware of the messenger effect, I am also more likely to be on my guard. Anytime I feel myself being attracted to a particular opportunity recommended by someone, I will try to take a breath and be critical.

3. Savings

We all need to save money for a rainy day, be it to protect against the possibility of losing our main source of income or to have a cushion to lean on in the event of a financial emergency.

Yet, more than 4 out of 10 Americans have less than $1000 in savings[1]. Given how important savings are for our financial health, why are so many people failing to build a rainy-day fund?

The Empathy Gap

When we make decisions when we are happy or sad, we usually don’t think about how those decisions will affect us when we are in a different headspace. This is known as the empathy gap, and it is one cognitive bias I fall prey to time and time again.

For example, when you are feeling happy and you commit to a side project with a friend, you are not considering how future you will receive this news, especially if the future you is prone to feeling harried by a heavy workload.

Similarly, when you need to save for a certain future purchase, it can be easy to postpone this decision, banking on future “you” summoning the willpower eventually.

🚗 For Example

When you need to save money to buy a new car, you can wake up today and tell yourself, “Today is a hectic day, so I won’t limit my spending. Instead, I will start saving tomorrow when I’m in a better mood and things are more settled.”

The problem is that tomorrow comes, and we are still not in the right mindset to start saving.

Temporal Discounting

The farther away a reward is, the less valuable it becomes to you. This is known as temporal discounting.

Put differently, most people would rather receive a reward this very instant than have to wait a while for a larger one. So, if you offer someone either $900 today or $1000 in six months, they will most likely opt for the $900.

The problem with temporal discounting is that it can lead you to make poor choices, with saving being a clear example of this. And, when you pair it with the empathy gap, you can see how psychological factors can derail your savings efforts.

4. Investing

Investing is all about buying assets today in the hopes of getting a great return tomorrow. And, we all need to invest, be it to secure our children’s future or to give us some wiggle room when we retire.

That said, you need to know that when you invest your money, you run the risk of losing some of it along the way. The trick is to make sure that your wins outpace your losses over the long term, and that requires psychological discipline.

Sunk Cost Fallacy

Have you heard the expression, “Don’t throw good money after bad?”

It mostly comes from the sunk cost fallacy, which describes our tendency to put more time, money, and effort into something we’ve already invested in. The problem is that a lot of the time, that initial investment might have been a bad idea, and sinking more money into it is just wasteful.

📉 For Example

Take a piece of stock you bought a month ago but that has been tanking ever since. This decline in the stock’s value might be due to market fluctuations or due to the stock being a bad pick in the first place. In either case, what you don’t want to do is invest more in the stock in the hopes of making up your losses when the stock picks up eventually.

But, when you think about it, the sunk cost fallacy sort of makes sense. We are loss-averse creatures, and we like holding on to the hope that any loss we incur isn’t permanent. And, is there any story better than a comeback?

We Are Not Psychologically Tuned to the Environment of Investing

Investing is hard, and most stock traders lose money.

For one thing, the stock market is a chaotic environment, where you might do everything right and still lose money. Alternatively, you could make every mistake in the book and still walk away a winner.

The problem is that too many investors give themselves too much credit when they succeed without realizing the role luck had to play in their good fortunes.

What’s even worse is that some investors might choose to change their investment strategy based on their winners and losers, which is also known as “resulting“.

🤔 You need to remember the following:

- Even the best investing strategy is still probabilistic in nature. So, if you have a 70% chance of making a profit this year, that still means a 30% chance of losing money.

- The future can be very hard to predict, and when it comes to the stock market, investors are closer to weathermen predicting the weather than doctors reading off an MRI.

The most effective way to counter cognitive biases in investing is to develop a strategy – ideally with professional advice – and stick to it.

5. Protection

Protection explores the different ways you can secure your financial future. This can mean buying insurance to protect yourself from possible calamities, or it can entail buying annuities to make sure your loved ones are taken care of should anything bad happen to you.

By now, though, part of you should realize that people are really bad at sizing up losses, making them happy to pay huge sums just to avoid the proverbial paper cut.

Prospect Theory

Prospect theory, which was the theory that landed Kahneman the Nobel prize, details how we can be irrational when it comes to protecting what is ours. The theory looks at how individuals make decisions involving risky options and the possibility of loss.

So, what does it say?

We are too risk-averse when it comes to losses at the low end of the probability spectrum.

On average, we tend to guard against losses by giving small probabilities too much weight. For instance, when you get a new dog, it might be extremely healthy, coming from an excellent pedigree. Nevertheless, you would be happy to pay monthly insurance premiums for your furry friend just to safeguard against the unlikely event of them getting sick.

Put differently, if there is a 5% chance of something bad happening, we would happily pay money to bring that number down to 0%.

We are too risk-seeking when it comes to losses at the high end of the spectrum.

At the other end of the spectrum, we can be too risk-seeking when we are all but sure that something bad is about to happen.

🤔 For example, imagine the two following scenarios:

- There is a 95% chance that you will lose $1000 and a 5% chance that you won’t lose anything.

- There is a 100% chance that you will lose $900.

Which of these two scenarios do you prefer?

From a pure numbers perspective, you ought to prefer scenario (b). But, most people will take the risk and go after scenario (a) instead.

We tend to be risk-seeking when it comes to losses at the far end of the spectrum, hoping that whatever meager chance we have will be enough to stave off a loss.

To top it all off, people are more influenced by percentage changes at the ends of the spectrum than by changes in the middle.

🤔 For example, imagine the following two scenarios:

- I tell you that the probability of something bad happening went down from 55% to 45%.

- I tell you that the probability of something bad happening went down from 10% to 0%.

Although the two above scenarios are equivalent from a mathematical standpoint, they don’t feel the same psychologically. Most people will tell you that they’d much rather prefer scenario (b) to scenario (a).

What’s more, if you asked people how much they would be willing to pay in each scenario to lower the probability by 10%, they would be willing to pay much more in the second scenario compared to the first.

Tackling the Psychological Factors Affecting Your Financial Decisions

There are several things you can do to protect your financial decisions from cognitive biases.

1. Learn About Behavioral Finance

When the field of finance started out, the initial assumption was that we are all rational human beings looking to maximize our happiness. However, as time has shown us, that is rarely the case.

And, this is how the field of behavioral finance was born. It combines finance and psychology, all the while investigating the different psychological forces that can impede our decision.

Try reading about it as much as you can so that you can anticipate the types of biases you are liable to meet during different situations and decisions.

2. Avoid “Resulting” and Have a Strict Process

Remember that almost any financial decision you make is probabilistic in nature. So, don’t give yourself too much credit when you win, and don’t be too hard on yourself when you lose.

Instead, you need to develop a strict process and stick to it. You can always revisit your process later on, but make sure that the reason you are amending things isn’t due to a sudden win or loss.

Instead, you want to try to adopt a long-term view and change your process when your aggregate results aren’t to your liking.

3. Use a Ulysses Contract If You Have To

In Homer’s The Odyssey, there’s a part where Odysseus, also known as Ulysses, and his men are about to pass through siren-infested waters. To resist their siren song, Ulysses asks his men to tie him to the mast of the ship and to keep him tied till they safely pass the dangerous waters.

This, in general, is what a Ulysses contract is. It is a way for you to stay committed to your goals by restricting your actions and preventing yourself from deviating from your plan.

The best example of an effective Ulysses contract comes from the world of dieting. Let’s say you decide you want to be healthier, so you commit to cutting sugar and unhealthy carbs from your nutrition. To that end, you go around your house, collecting any product that has a whiff of sugar in it, and you give it all to charity or goodwill. The point is that you take all that unhealthy food and toss it out of the house.

So, with no more access to sugary food, you will no longer be tempted.

Similarly, when making a financial decision such as saving or controlling your spending, you want to make sure that you get rid of any temptations that can stall you from reaching your financial goals.

4. Leverage the Tools of Scenario Planning

When striving for a particular financial goal, you might want to use different techniques used by scenario planners, including backcasting and premortems.

Backcasting asks us to imagine a future where we achieved our goals. Once there, we want to figure out what it took to get us to this point. In other words, if you are able to buy a new car for your family one year from now, what has to be true today for that future to become a reality?

Premortems take a different look at things. They ask us to imagine a future where we failed to reach our goals. Mentally placing ourselves in that unfortunate scenario, we need to think of all the things that could have gone wrong and led us astray. Again, if you wanted to buy that new car but found that there wasn’t enough money in the budget for it a year from now, what happened between then and today that stopped you from saving the required amount?

Putting It All Together…

No matter how hard you try, cognitive biases will impact you and affect your financial decisions, whether you are budgeting your money or planning your next investment. The trick is to minimize the damage they do to your personal finances.

This starts by knowing yourself and being aware of the biases most likely to trip you up. Moreover, there are plenty of tools at your disposal to help you sidestep the worst of potholes.

And, remember, brains have nothing to do with it. Even the smartest people on the planet make thinking errors without realizing it!